Can Childhood Trauma Make Us Age Faster?

4 min read

49,733 views

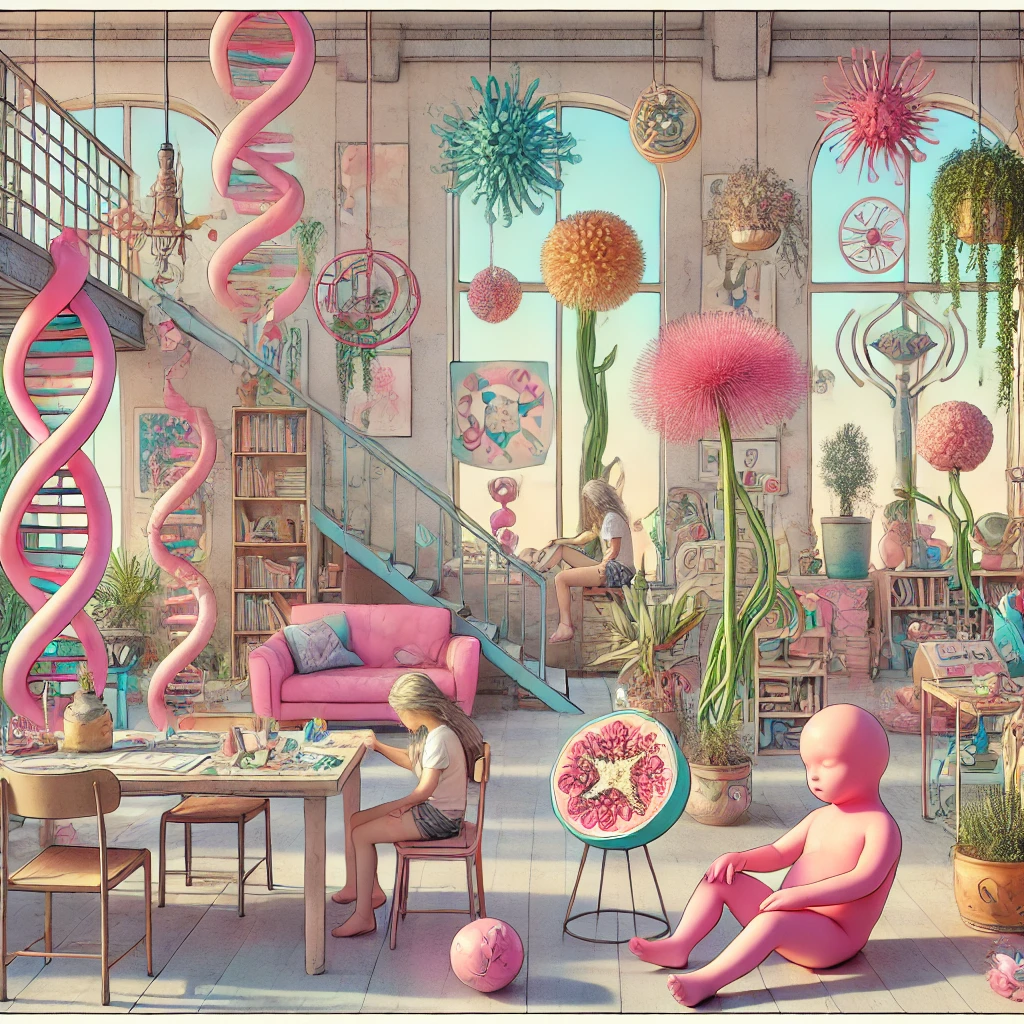

Can Childhood Trauma Make Us Age Faster? How Stress Affects Our Cells and Our Health

We've all heard that stress can take a toll on our health. But did you know that traumatic experiences in childhood might actually speed up the aging process? New research is shining a light on how childhood adversity can affect our cells, potentially leading to premature aging. Specifically, these studies point to the role of mitochondria and telomeres in this process—two key players in how our bodies age at the cellular level.

The Powerhouses of Our Cells: Mitochondria

Mitochondria are known as the "powerhouses" of our cells because they produce the energy that fuels everything from muscle function to brain activity. But recent research, published in Science Advances, shows that mitochondria may also be sensitive to the emotional and psychological stress we experience in life, particularly in childhood. The study looked at older adults and found that those who had experienced more adverse childhood events (ACEs), such as physical or emotional abuse, had lower mitochondrial energy production later in life.

This reduced mitochondrial function was linked to lower ATP production — a crucial energy molecule that powers muscle function. As a result, people who went through childhood trauma might face more rapid physical decline as they age, with weaker muscles and a higher risk of age-related diseases like frailty and mobility issues.

The Telomere Connection: Another Piece of the Aging Puzzle

Adding to the evidence, another study by Aas et al. found that childhood trauma also affects telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of our chromosomes. Telomeres shorten as we age, and when they become too short, cells can no longer divide effectively, leading to cellular aging and death.

This study showed that people with severe mental disorders, like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, who had experienced childhood trauma, had significantly shorter telomeres than those without trauma. Shorter telomeres are considered a marker of "biological aging," meaning that childhood trauma might accelerate the aging process at a molecular level. Even in people without mental disorders, previous research has shown that chronic stress and trauma can lead to faster telomere shortening, contributing to a range of age-related health problems.

How Do Stress and Trauma "Get Under the Skin"?

Both studies suggest that stress, especially in childhood, can "get under the skin" by impacting key biological systems. Chronic stress leads to higher levels of cortisol, a hormone that, when produced in excess, can damage the mitochondria and contribute to inflammation—another factor linked to faster aging.

Telomeres, too, are sensitive to stress. They are thought to act as a "molecular clock," and when childhood trauma accelerates their shortening, it speeds up the aging process at a cellular level. This dual impact—on both mitochondria and telomeres—highlights the profound effect early-life stress can have on our long-term health.

What Can We Do About It?

While the effects of childhood trauma can be long-lasting, there are steps we can take to support healthy aging. Exercise, for example, is known to boost mitochondrial function, while certain dietary interventions, like consuming antioxidants, may help protect telomeres from damage. Stress management techniques, such as mindfulness and therapy, can also help reduce the long-term impact of trauma by lowering cortisol levels and inflammation.

Conclusion: The Hidden Cost of Childhood Trauma

The evidence is clear: traumatic experiences in childhood can affect our health in ways that last a lifetime. By impacting both our mitochondria and telomeres, childhood stress may make us age faster at a cellular level. But understanding these mechanisms also opens the door to new strategies for promoting healthier aging—proving that it’s never too late to take action and protect our cells.